In September, we recognize Childhood Cancer Awareness Month. More than 15,000 Americans under the age of 20 are diagnosed with cancer annually, yet in the last 38 years less than ten drugs have been developed for use in children. According to the National Pediatric Cancer Foundation:

- More than 95% of childhood cancer survivors will have a significant health-related issue by the time they are 45 years of age. These health-related issues are side effects of either cancer or, more commonly, the result of its treatment.

- Cancer is the number one cause of death by disease among children.

- Only 4% of federal government cancer research funding is dedicated to studying pediatric cancer.

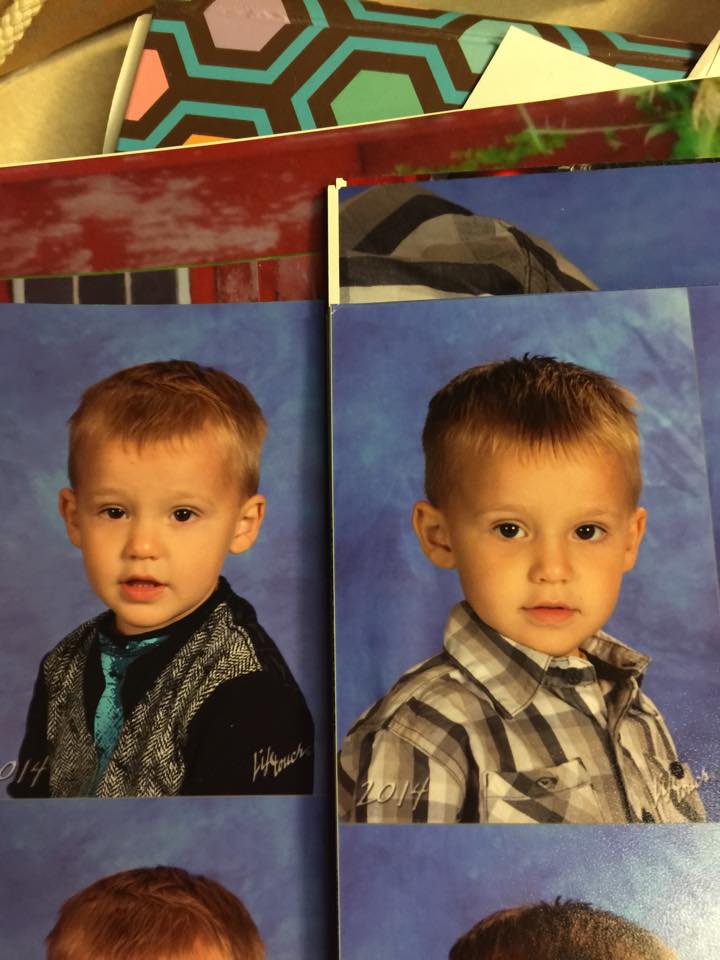

Recently, I sat down with my friend Joscelyn Laurence to talk about her experience with childhood cancer and her son River’s ultimate demise due to cancer at the age of four. I met Joscelyn at the first La Leche League breastfeeding support group meeting I attended when I moved back to Texas in 2014 after two years in Korea. I was so excited to be back in San Antonio, and as a long-time leader I was excited to meet the new leaders in San Antonio. Joscelyn was—and still is—an ultra cool mama with tattoos and piercings, who, on the day I met her, happened to be pregnant while holding the hand of an adorable three-year-old River. Just a few months later, she became the mama of a sweet newborn and a son recently diagnosed with high-risk stage 4 neuroblastoma. In a weird twist of fate, I suddenly had a friend whose child had the same type of cancer that my brother died from when I was a child, so as you can imagine, it really hit home.

In the realm of cancers, neuroblastoma is a common childhood cancer, most often diagnosed between age one and two and infrequently after age 10. Depending upon the stage at diagnosis, survival rates are as high as 95%. According to the American Cancer Society, the survival rate at stage 4, though, is 40–50%.

Joscelyn recalls that back in October 2014, one of River’s teachers was the first to notice that something was wrong with River, telling Joscelyn and her husband that he had been limping at school. Of course, when they picked him up, River went running off to play without a limp. Later that evening, he told them that a kid at school had kicked him and that is why he was limping. Periodically over the next month or so, River’s teacher would ask if his parents had gotten the limp checked out, but because it was so sporadic they hadn’t sought medical evaluation. Finally, in November, Joscelyn and her husband took River to the chiropractor thinking his hips needed to be adjusted. Shortly after that, they noticed one of his lymph nodes was protruding, so they went to a chiropractor again. The chiropractor thought River had a bowel obstruction and sent them to a free-standing emergency room for an ultrasound. After discovering a softball size mass on the ultrasound, the provider sent River to a traditional ER. Just by sheer chance the doctor they saw there had already diagnosed a child with neuroblastoma a couple of years before and recognized what he saw. The diagnosis was formally confirmed the next morning.

The Laurence family chose to pursue treatment in San Antonio the first year, starting chemotherapy on Black Friday. After almost a year of treatment, River was not getting worse but also not improving. The Laurences decided to look for other treatment options and ended up at Cook Children’s Hospital in Fort Worth. They were there for another six months with no changes. The doctor there felt River would benefit from surgery and suggested three locations that offered the specific type of procedure, one of which was Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York, which is considered the best place for neuroblastoma treatment in the U.S. Joscelyn feels this was the beginning of the end, partially because of the surgery specifically and partially because of how hard on the cancer and its treatments were on River’s body.

For the next year River battled infection after infection in his bladder and kidneys. Joscelyn says that “science and medicine were not where they needed to be to help River. All of the devices that had been developed to treat River’s issues were for itty bitty babies or adults [not someone his age and size].” River ultimately died on June 15, 2017. River did not die of cancer, but ultimately, he died from cancer and the devastating effects of treatment on his body. Joscelyn wants people to know this. His death certificate lists neuroblastoma as the fourth cause of death. Three other causes are listed above the cancer.

Looking back, Joscelyn says they did what they thought was best for River and they can’t have any regrets. “Maybe we made wrong decisions sometimes, but we always made the best decision we could with the information we had at the time,” she explains. “That’s the biggest thing—being a parent, you are always going to be judged for something. You did not breastfeed. You did not cloth diaper. You worked or you didn’t work. Cancer is just like that. If you are open with your story, people who know nothing about cancer, who have no idea, judge decisions we made.” She says you cannot listen to those things. “You have to follow your heart. There are not necessarily bad decisions. You can only know so much about what’s going to happen.”

Joscelyn is taking it one day at a time in the 14 months since River passed away. “It is harder today than it was the day River died,” she confesses. “There is nothing as awful as losing your child.” Heartbreakingly, she admits that if not for her daughter Sparrow, she would not be here; the grief is so strong. “But Sparrow is so special,” says Joscelyn. “And she’s already lost a brother. I don’t want her to lose a mother too. She is sassy in a different way than River was. She is funny and has a big attitude. I am here for her.”

When you ask Joscelyn what supported her the most, she thinks of several things. The first, however, was babysitting. Being a mother with an infant and a preschooler with cancer meant she was stretched thin. Her husband could not always be there because he had to work. People brought coffee, meals, and activities to keep her and her children busy and fed during the long hours, and it made a huge difference. These little things let the Laurence family know people were thinking of them. “It sounds silly maybe, but when our friends all changed their profile picture on Facebook to this special image that said #TeamRiver, it meant so much,” she says. When people tagged them in posts that said things like “thinking of little River who is undergoing chemo today,” it made a hard day much easier for Joscelyn and her husband. “It made me feel so good to see my feed fill up with these positive thoughts,” she adds.

Support groups also made a huge difference for Joscelyn. She met with several weekly and monthly groups at Cook Children’s Medical Center in Ft. Worth. “No other hospitals we were at had this kind of support, and it was hard,” she says. “Being a parent of a child with cancer can be lonely, and these group really helped. I missed them when I was elsewhere.”

Right away when River was diagnosed Joscelyn saw all of the amazing things people were doing for families with cancer and knew one day they would also do something to give back. Her thoughts on what form it would take, changed throughout their journey with River. But now Joscelyn has a clear picture. She has formed a 501(c)3 called River’s Rainbows with the tagline “Let’s Talk About Pediatric Cancer.” And talking about pediatric cancer is exactly what she wants to do, in two ways.

First, Joscelyn wants to bring the support groups that meant so much to her in Ft. Worth to San Antonio. “Those were so helpful,” she says. “That is where I met one of my best friends.” She explained that here in San Antonio, we have three hospitals that include pediatric oncology, but they are owned by three different companies. If two families each have a child with neuroblastoma, unless they somehow meet through a common friend, they may never know each other. “I can kind of compare what I want to do to La Leche League. All the mothers [in the League] are unique and from different places in the city, but we are all breastfeeding. That is what brings us together,” she explains. “This is how it is as the parent of a child with cancer. It can be very isolating, and no one else understands your experiences like another parent of a child with cancer.”

Second, Joscelyn wants to bring awareness to pediatric cancer. “It is part of my healing process, not letting River’s death be in vain. He has a legacy that I am carrying on,” she says. “Many people never know a kid with pediatric cancer, so I want to tell them about it and what needs to be done to cure it.” According to Joscelyn, federal funding for pediatric cancer research is just 3.8%. If we do not fund research, we will never improve treatments or find a cure. Privatized research will cure cancer in the end. When River was diagnosed, only one drug in 20 years had been approved specifically for the treatment of cancer in children. This means most kids get the same drugs as adults even though their bodies react differently.

Joscelyn does not want River’s Rainbows to collect money for research. She wants to bring awareness to all of the amazing organizations that are out there already doing it, like Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, St. Baldrick’s Foundation, and Cookies for Kids Cancer™. This month, in honor of Childhood Cancer Awareness Month, she is working with Alex’s Lemonade Stand. She is also setting up a Hero Fund with St. Baldrick’s Foundation, which she has been involved with since River’s diagnosis. A Hero Fund stays in place year-round, and the person setting it up can designate where the funds go. “The monies raised in this fund will go directly to neuroblastoma research. I care the most about this cancer because of River. Cancer is not [all the same]. And I hope to make a difference for another child with neuroblastoma,” she explains. “Many hospitals have research foundations. Cook Children’s has a neuroblastoma fund. You can send your money directly to them to fund their research there. I feel so strongly about the privatization of research because that is where the cures will be found.”

The first big contribution to River’s Rainbows came from firefighters with the San Antonio Fire Department who sold Fiesta medals in River’s honor during Fiesta this past year. This means so much to Joscelyn because firefighters meant so much to River. He was even sworn in as a firefighter at the Converse, Universal City, and New York City Fire Departments. Joscelyn looks back at his love of firefighters and says, “Maybe it was a normal little boy thing. He just wanted to go up to the station and wash the trucks and hang out. He got such joy just being at the fire station.”

Despite all of the heartbreak, Joscelyn would never give up the time she had with River. Her main wish was they could have had more time or that doctors could have cured him of his disease without so many deadly side effects. “The only way that [could] have happened is with more research in pediatric cancer,” she says.

If you are interested in supporting Texas families with children diagnosed with neuroblastoma, please check out #erasekidscancer, a special fundraising campaign that Cook Children’s Hospital is highlighting this month to raise money specifically for childhood cancer research. Or, follow River’s Rainbows on Facebook to keep up to date with Joscelyn’s journey as she supports other parents of children with cancer.

❤️❤️❤️ Thank you for sharing. Wishing for healing and blessings to make up for all that team river went through. What a wonderful way to keep his legacy alive! I’m inspired to look into all of the organizations mentioned here and give back, too.